Cruciate Ligament Disease in Dogs

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is commonly torn in people. Dogs, like humans, often rupture this ligament that is more properly called the cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL) in dogs. Unlike humans, this tear is often the result of subtle, slow degeneration that has been taking place within the ligament rather than the result of trauma to an otherwise healthy ligament. This is why approximately half of the dogs that have a cruciate ligament problem in one knee will, at some future time, develop a similar problem in the other knee. Also, in contrast to humans, the skeletal structure of the dog knee is such that the CrCL is under a tremendous mechanical stress even during relatively sedentary activities. The human knee does not operate at an angle like the dog knee. Unfortunately, this also means that ligament replacement techniques, as frequently performed in the human patient, have a unique challenge in the dog!

Structure of the knee joint

As can be seen from the figure, there are 2 ligaments that cross over in the knee. The one in front is the Cranial Cruciate Ligament and is the one most often torn. The 2 cartilage “cups” that cushion the joint are called the meniscus. There is one on the inside aspect of the joint (medial meniscus) and one on the more outer aspect, the lateral meniscus. The medial meniscus is often damaged/ torn in cruciate rupture. Sometimes this is evident at the time of surgery as a tear, and sometimes it only becomes evident weeks or months after surgery.

How do we diagnose cruciate rupture?

Diagnosing cruciate ligament degeneration/tears is usually very simple with observation of your pet’s gait, palpation of your pet’s knee and x-rays. At times, however, it is more complicated and may require advanced imaging such as MRI or surgical exploration through a traditional surgical arthrotomy or with the use of a minimally-invasive arthroscope. The most common diagnostic sign is called the presence of a “cranial drawer sign” in the knee. This is purely a forward movement of the shin bone (tibia) on the thigh bone (femur). Many cases this can be evidenced during normal examination, but it may require sedation or anaesthesia to relax muscles to perform a proper examination.

Choosing which CrCL surgical treatment is best for your pet

Our philosophy is to offer a variety of surgical treatments for CrCL tear and do our very best to work with you, the pet owner, to tailor our treatment recommendations to the unique needs of your pet and family. Variables that we take into account when making our recommendations include your pet’s activity level, size, age and conformation, the degree of knee instability, and each option’s affordability in your family budget. Surgical procedures of the knee are among the most commonly performed in our hospital.

Surgical options

- Extra-capsular suture stabilization (also called “Ex-Cap suture”, “lateral fabellar suture stabilization” and the “fishing line technique”)

This is a traditional surgical treatment that has been performed for many years. The concept of this procedure is to replace the function of an incompetent cranial cruciate ligament with a heavy monofilament nylon suture placed along a similar orientation to the original cruciate ligament, but outside of the joint (the actual ligament is inside the joint). The suture needs to stabilize the tibia (“shin-bone”) relative to the femur (“thigh bone”), while allowing normal knee movement, until organized scar tissue can form and assume the stabilizing role. These techniques tend to have a little bit too much “give” for larger breeds and active dogs, but seem to work reasonably well in small breeds and inactive dogs when performed by an experienced surgeon. Postoperative care at home is very critical and involves strict activity restriction initially. Premature and excessive activity risks complete or partial failure of the stabilizing suture that can render the surgery a complete or partial failure.

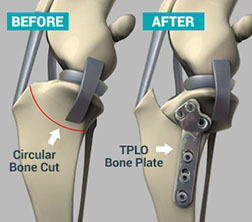

2. TPLO

Evidence now shows that altering the angle of the Tibial Plateau achieves better short and long term outcomes in cases of cruciate disease. This procedure involves cutting the top end of the tibia in a semi-circular cut and rotating the joint surface around into a more upright position. This then causes less shear force with each step. This cut is then stabilised with a special plate and screws. We are one of only a few clinics in Perth performing this top end procedure for cruciate disease.

3. Other surgical procedures

These include the TTA (which we do perform) and the TTO. In essence the TPLO supersedes these although there are still cases where perhaps a TTA would be preferential. This decision is generally made after performing X-rays.

Non-Surgical Options

Activity restriction, weight loss and anti-inflammatories – This combination is not a treatment per se because it does not stabilize the knee. This regimen may allow the knee joint inflammation to subside somewhat. While the symptoms of lameness and pain may subside with time, attempts to return to normal activity levels will often be limited by the progression of osteoarthritis. In general, we do not advise this therapy as the ideal form of treatment, but it may be appropriate for individual dogs due to some combination of their very small size, inactive lifestyle, other concurrent injuries or diseases, or financial realities. It is important to point out that, in general, the earlier surgical therapies are performed, the more effective they are; thus a “wait and see” approach to non-surgical management based only on wishful thinking is seldom advised. Once osteoarthritis sets in, it cannot be reversed through any of the surgical approaches.

Rehabilitation therapy, custom knee bracing, etc – There is ample evidence that peri-operative rehabilitation therapy by a trained rehabilitation practitioner can advance and hasten the recovery from surgery. There is little/no evidence to suggest that this is a consistent and predictable alternative to surgical management for most dogs, but occasionally the combination of concurrent injuries or diseases, advanced age, patient size and financial limitations lead pet owners to pursue this option. Custom knee bracing is relatively new to canine orthopaedics and there is little/no scientific evidence on the topic applied to cruciate ligament injuries.

Possible complications of cruciate treatment/ surgery

It is very important to note that whilst every attempt is made to treat or repair cruciate injury, none of the above treatments or surgery will bring the knee joint back to 100%. Thus, over time, the onset of arthritis in the joint is inevitable. How rapidly this sets in and advances is variable, however, in most cases, a surgical approach to treatment, lessens this onset but does not negate it all together.

Before making any decision to proceed with surgery in any pet, it is important that you, the pet owner, are aware of the possible complications of surgery in these cases. Whilst complications are rare, they do happen and in some cases, may result in subsequent surgery being needed.

These possible complications can be:

Infection

Whilst every effort is made to prevent this from occurring (sterile operating environment, intravenous antibiotics and dispensed antibiotics), sometimes infections do occur and can be difficult to clear. Most infections occur from self-trauma (licking at wounds etc) and environmental contamination (dirt on wound etc). It is thus very important that an Elizabethan collar is kept on your pet and that you keep your pet indoors during the initial recovery stage.

Non-union of the bone

This refers specifically to the surgeries involving surgical cutting of the tibia and using plates and screws. It is very rare but can occur when bone healing just does not progress as expected in individual cases.

Meniscus damage

As mentioned previously, this is something that can be evident at the time of surgery, but can also occur weeks to months after surgery. It is the most common cause of lameness in patients after surgery. Further surgery is required in these cases to remove the torn cartilage otherwise pain and thus non-use muscle atrophy in the leg occurs.

Nerve damage

This is an extremely rare complication of surgery, but can occur when healing and inflammation of the tissues surrounding the knee joint impact on the nerves in the area. Scuffing of the toe nails when walking is the most common sign of this.

Hardware (i.e. plates and screws or monofilament suture) loosening and/ or failure

Very rarely do we see loosening of the screws in the plate, but this can occur, especially if too much activity occurs in the beginning. Breakage of the plate can also occur as well as rupture/ snapping of the monofilament loop. Further surgery is then required in these cases.

Fracture of the tibial crest

This only pertains to the surgeries where cuts are made to the tibia. The knee-cap ligament attaches to the tibial crest and in patients where too much activity occurs too soon after surgery, the patella ligament can cause the end of the tibial crest to fracture. Once again, further surgery will be required in these patients.

Anaesthetic complications

Whilst every endeavour is made to limit these (pre-anaesthetic checks and blood tests, fluids, advanced monitoring, up to date anaesthetic protocols), we do see many variable complications arising from anaesthesia similar to those experienced in the human surgical field.

Whilst, as mentioned, complications are rare, the above are the most commonly seen or experienced.

Please feel free to discuss any concerns or questions you may have with one of our veterinarians at anytime.